Glitch Hunt - My js13kGames 2016 Entry

If you've read my blog previously, you might recall that last year, I entered js13kGames. Since 2015's competition, I've been itching to make more games, learning new techniques with each release; naturally, I entered again this year.

If you have no idea what I'm talking about, js13kGames is a contest in which participants create games using JavaScript and other web technologies, with the main caveat being that submissions can't surpass 13 KB in size once compressed. That makes using existing engines such as Phaser practically improbable, adding to the typical challenges one faces during games development. Additionally, there's a theme that one is expected to follow.

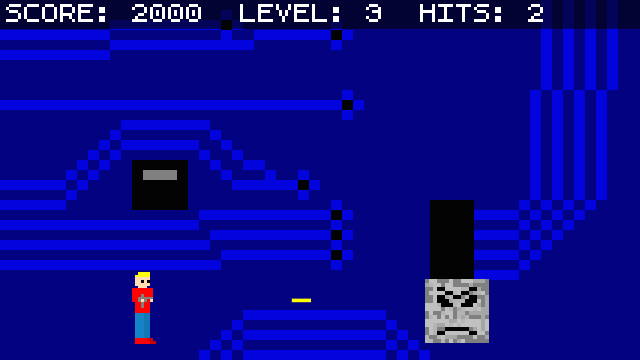

This year's theme was glitch, which admittedly threw me aback; while my immediate idea was to create a game with visual glitches, I decided that I should make it central to the gameplay. After some planning, I came up with Glitch Hunt. The idea is that the player must hit the keys on their keyboard at the right time, which is my attempt of emulating the live patching of a system; it's heavily inspired by those old dance mat games. Since I thought this alone would be too boring, I also threw in a boss battle that plays like a platformer.

I was able to take what I learned from last year's entry, as well as some of the incredible games against which mine paled, and make something that I deem to be substantially superior.

You can play the game on the js13kGames site, and the source code is available on GitHub.

Separating Concerns

After failing to use an architectural pattern last year out of concern that it wouldn't fit within the 13 KB limit (read: laziness), I vowed to separate the code of my subsequent games properly. A brief Google search pointed me to Entity Component System (ECS), a pattern that favours composition over inheritance. After using the pattern to develop a Breakout clone, only to be informed that I had misunderstood the responsibilities of components and systems, I was pointed to the work of Richard Lord, a veteran game developer who wrote Ash, an ActionScript implemtation of ECS. Richard breaks down ECS as so:

- Component - wrap properties into objects so that they can be shared between entities and systems

- Entity - a collection of components

- System - updates entities that contain a certain component during each iteration of the game loop

Of course, I only had 13 KB with which to work, so I had to make it more lightweight. Here's the init method for my Player entity:

Player.prototype.init = function init() {

G.spriteAnimatable.deregister(this);

G.positionable(this, X, Y, WIDTH, HEIGHT);

G.imageRenderable(this, this.getSprite);

G.keyboardMoveable(this, SPEED);

G.jumping(this, Y, JUMP_SPEED);

G.shooting(this, 'bullet', SHOOT_Y_OFFSET);

G.hurtable(this, HEALTH);

G.collidable(this);

};

You can infer from the name of the components (spriteAnimatable, positionable etc.) that the Player entity is a collection of behaviours which can be reused elsewhere. So how does this work? Let's take a look at the imageRenderable component:

G.imageRenderable = function imageRenderable(entity, image) {

entity.image = image;

G.imageRenderSystem.register(entity);

};

To save space and to assist with performance, I'm directly mutating each entity that calls this function before registering it with a system. To summarise, my implementation of components ensure that the required properties are defined and initialised with the correct value, or an appropriate default. I then register this with imageRenderSystem:

function ImageRenderSystem(context) {

this.context = context;

}

ImageRenderSystem.prototype = G.system.create(function next(entity) {

var image;

if (!entity.isHidden) {

image = entity.image instanceof Function ? entity.image() : entity.image;

this.context.drawImage(

image,

G.getScreenXPos(entity.x),

G.getScreenYPos(entity.y),

G.getScreenXPos(entity.width),

G.getScreenYPos(entity.height)

);

}

});

G.system.create is a method that abstracts Object.create, as well as attaching common methods to each system. The next callback is invoked during each interation of the game loop, and for each entity that is currently registered with the system.

The ImageRenderSystem assumes that the entity implements the positionable component, which is a lightweight alternative to writing wrappers to share object references.

Here's how the game loop looks:

function gameLoop(timestamp) {

G.renderingContext.clearRect(0, 0, G.renderingCanvas.width, G.renderingCanvas.height);

G.imageRenderSystem.update(timestamp);

G.spriteAnimationSystem.update(timestamp);

[...]

G.collisionSystem.update(timestamp);

G.flashSystem.update(timestamp);

requestAnimationFrame(gameLoop);

}

requestAnimationFrame's timestamp is passed to each system in case it is required for computation e.g. frame rates for sprite animations, calculating the player's rate of fire etc. This code definitely needs work, but it's my best attempt thus far, and really eradicated duplicate code. My next goal is to take these concepts to ES6-land.

Pixel Art

One key take-away from the 2015 contest was to use small, pixel-intensive art and scale it up. Greg Pabian used this in his entry, Captain Reverso, and I thought it looked excellent. I took the same approach this year and achieved decent results. Here's how the player looks in the game:

(D'oh! Looks like his right eye is a bit off - guess that's what happens when you're dealing with world space!)

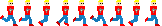

And here are the stationary player sprites at actual size:

Using this approach allows for both an old-school aesthetic and greatly reduced file sizes. Just remember to set your CanvasRenderingContext2D's imageSmoothingEnabled property to false!

On the note of file sizes, it's well worth encoding your images with Base64. Although they will be slightly larger than your initial files, ZIP compression algorithms are much better at compressing text than images, leading to bigger reductions later on. Additionally, you can reduce your sizes further by using an image optimiser before encoding, such as TinyPNG.

The Sprite Sheet

For easily accessing different sprites that were grouped in an image, I wrote a sprite sheet implementation. It determines the number of frames by an image's overall width and the intended sprite width. Each frame is then rendered onto another CanvasRenderingContext2D instance, which is then requested as a PNG and attached to the sprite sheet instance's sprites array. This is done at start-up to avoid lagging during the game:

for (var i = 0; i < this.spritesCount; i++) {

imageData = G.spriteSheetContext.getImageData(i * this.spriteWidth, 0, this.spriteWidth, this.spriteHeight);

G.individualSpriteContext.putImageData(imageData, 0, 0);

image = new Image();

image.src = G.individualSpriteCanvas.toDataURL('image/png');

sprites[i] = image;

}

Sprite-Based Font

To keep in line with the 8-bit aesthetic, I looked for retro-themed TTF files. Big mistake; upon optimisation, the smallest I could find was 10 KB. Therefore, I had to write my own font, which is a sprite sheet. Here's a black version of the font:

This is scaled up just like other images, and the TextRenderSystem utilises character code offsets to render the request characters:

TextRenderSystem.getSpriteIndex = function getSpriteIndex(char) {

var charAsNumber = parseInt(char);

if (!isNaN(charAsNumber)) {

return ZERO_INDEX + charAsNumber;

}

return specialIndices[char] || char.charCodeAt() - A_CHAR_CODE;

};

There's also a map of special indices, such as spaces and question marks.

Sprite-Based Animations

An absolute must for me was to implement better animations, so I drew two sprite sheets for the player running left and right respectively:

The SpriteAnimationSystem determines when to update the sprite according to the defined frame rate:

SpriteAnimationSystem.prototype = G.system.create(function next(entity, timestamp) {

var frameDurationMs = ONE_SECOND_MS / entity.frameRate;

if (timestamp - this.lastFrameTimeMs > frameDurationMs) {

this.currentFrame = this.currentFrame === entity.spriteSheet.spritesCount - 1 ? 0 : this.currentFrame + 1;

this.lastFrameTimeMs = timestamp;

}

entity.image = entity.spriteSheet.get(this.currentFrame);

});

Sound

Pushing myself further, I really wanted to include music and sound effects this time round. I wrote a small music schema and library called NanoTunes, which enabled me to compose songs with a few characters; the library uses OscillatorNode, removing the need for low-quality, heavily compressed MP3 files.

I also used OscillatorNode to generate sound effects:

jump: function jump() {

var oscillatorNode = context.createOscillator();

var gainNode = context.createGain();

oscillatorNode.type = 'square';

oscillatorNode.frequency.setValueAtTime(100, context.currentTime);

oscillatorNode.frequency.exponentialRampToValueAtTime(200, context.currentTime + 0.3);

gainNode.gain.value = 0.1;

oscillatorNode.connect(gainNode);

gainNode.connect(context.destination);

oscillatorNode.start();

oscillatorNode.stop(context.currentTime + 0.3);

}

As well as dramatically saving space, this complemented the 8-bit style of the game.

Room For Improvement

All that said, there were plenty of things that I could have done to improve my entry. Notably, my final ZIP was only 9.2 KB, giving me an extra 4 KB with which I could have taken my game ot the next level, such as:

- cutscenes

- a third gameplay mode

- high scores

The reason I decided to stop where I did was due to the immense burnout from which I'm suffering. In addition to the non-stop development of Glitch Hunt, I've been working on episodes for my SitePoint series on Web Audio, as well as engaging in other open source commitments.

One final point I'd like to raise is that I'm not convinced Closure Compiler was needed. I had a great deal of success with it for my JS1K entry, but in this case, I could have used Uglify in conjunction with Browserify, for example. You can see how nuts the build script, and managing those dependencies was initially tricky.

More Games

Overall, I'm really happy with Glitch Hunt, and I'm now itching to make more games. I have an idea for a mobile game, which I'm hoping to start working on next year.